Al and Nancy Barile on documenting the past and setting the record straight

Talking to two hardcore legends about bringing history to the present.

Despite having been obsessed with punk and hardcore for most of my life, I've never interviewed many of the icons from those genres. It's not because I find myself intimated—though maybe that's secretly true—but, in many cases, I feel like those people have been adequately documented. While I have an undying respect for Ian MacKaye, his status, coupled with his general availability, means that anything I'm curious about has already been answered, and then repeated, several times over. Even though I can identify him as the genesis of many values I adopted and steadfastly uphold, there's something about interviewing him that makes me feel like I'd only be doing it for vanity's sake.

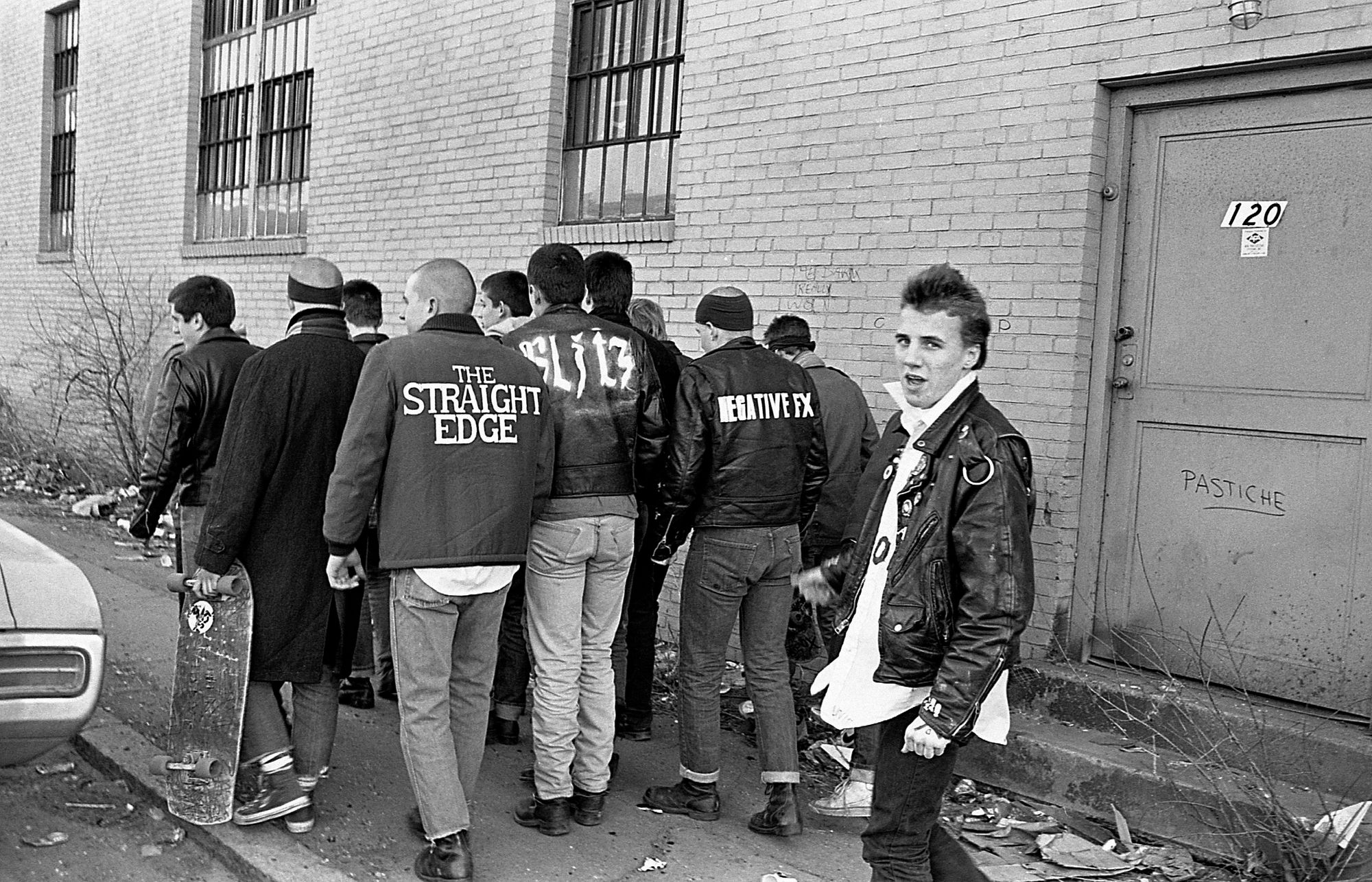

In the case of Al Barile and Nancy Barile, it couldn't possibly be more different. For one, Al's band SSD (Society System Decontrol) was a part of the Boston scene I became obsessed with, and his label XClaim! Records was responsible for releasing some of my favorite hardcore albums of all time. Never mind the fact that his adherence to, and advocacy of, a straight edge lifestyle was a dominant reason for my choice to participate in that lifestyle for as long as I did. Meanwhile, Nancy was booking shows in Philadelphia and managing bands, bringing an early example of a do-it-yourself ethos to the way one conducts oneself, which is why she was always spoken of with such deep reverence by many of hardcore's early participants. As time went on, and both of them took steps back from the scene, it felt like they began to exist more as myths than people. That is, until recently.

In 2021, Nancy published her memoir I'm Not Holding Your Coat: My Bruises-and-All Memoir of Punk Rock Rebellion, a detailed look into the early days of American hardcore in a way that corrected many of the omissions from the previous generation's history books. It was followed this year by How Much Art Can You Take?, a book she organized featuring photos of SSD taken by legendary Boston photographer Philin Phlash, along with interviews and recollections from the band itself. Finally, and perhaps most notably, this Friday, Trust Record is reissuing SSD's debut album The Kids Will Have Their Say. Released originally in 1982, the album has been out of print since mere months after its release, becoming a highly sought-after record, and one that you'd previously only been able to acquire via bootlegs of varying quality.

With all of these things happening, it felt like Al and Nancy were returning to tell their stories one last time. It's why I'm thrilled to be able to discuss all of these things, as well as the motivations behind them, here on Former Clarity. I never thought any of this would happen, but I'm glad it finally has.

Knowing how much time it takes to get books and records released, when did you two first talk about putting these things together?

Nancy Barile: For my own personal book, I had won a couple of teacher awards and people would always ask me, “What makes you a good teacher?” When I really thought long and hard about it, it was my time in punk rock. I got so many skills and strategies from that time period. I'm an English teacher, so I always wanted to write a book. I sat down and I wrote a book that was about how punk rock made me a better teacher. Those were articles in Education Week that kind of went viral first. I was like, oh, I have something here. So I wrote about my punk rock life and my teaching life, and I got a high-powered New York agent and he was planning to put this out to auction. But what happened was, that people either liked the punk rock story or the teacher story, they didn't like them together. He ended up not being able to do anything with it, and it was easy for me to pull off the punk rock part because it was finite, it kind of ended towards the end of the ‘80s when I stopped being super involved in the scene.

I'm in a lot of punk rock and hardcore Facebook groups and every time I would post a story about something that happened on an anniversary date, invariably, some dude born in the ‘80s or ‘90s would come on there and be like, “Oh no, it didn't happen like this” at a show that I did. The mansplaining was unbelievable. I was just like, well, you know what, I'm gonna write the book. And when I was sitting down writing, I was like, these stories are crazy. I can't believe all this happened.

The book about SSD, that happened because, you know, Al had a very dedicated career for over 30 years with GE [General Electric], and they kind of treated him very badly at the end of his career when he had a lot of operations for his back. He was a little bit depressed, so I wanted him to see the impact that his band had on so many people around the world because I was a fan before I was a girlfriend or wife. I asked him if I could take over the SSD Facebook page, and I asked him if I could start an Instagram page. To make it authentic, since I'm not in the band, I only would print stories from the band or the people very close to them. That really took off and that's when I thought, well, this should be a book, too.

Al, did you still have a sense that people cared about SSD after all this time?

Al Barile: Yeah, I kind of wasn't surprised. But I mean, if you asked me back then, if you asked me back in 1981, “In 2023, would we be talking about SSD,” I would not have guessed we would’ve been. But I've been tracking it over the years. The first record, The Kids Will Have Their Say, came out in 1982, and within a few months, it was out of print. At that point, I could have ended my label and jumped to another label or something, but I felt that rather than reprint that record, I would focus on the next record. Immediately, we started focusing on recording Get It Away. When you take on a new project, it does suck up funds, and I didn’t have unlimited resources. I think I borrowed money from my parents just to make The Kids Will Have Their Say and I paid them back within two or three months. I think there's actually receipts that we found that prove that. I don't know how much I borrowed, but maybe Nancy could find it.

Nancy Barile: Yeah, I have it somewhere.

Al Barile: But I paid them back, and I wasn't gonna keep on asking them. Hopefully, I was gonna be able to make the second record without always going to them to get money. That's kind of why the record became out of print. Even within a year, there was some interest in it getting repressed. It certainly wasn't the interest that's been there in the last 10 years, but there was always an interest.

I think the band broke up in ‘85, something like that, so I loosely stayed involved in music a little bit just from a fan standpoint. Then I started thinking about starting another band, maybe around the early ‘90s. I still was going to shows and I had maintained a friendship with Ian from Fugazi. They came and played a show and stayed at our house. So, you know, I still was somewhat out there, but definitely not speaking. Whenever people would ask me for an interview, I’d remain silent. I kind of felt that I said a lot in the band and the lyrics and everything. I'd done a few key interviews during the four or five years we were together, so I thought I pretty much said enough and that, you know, people doing videos at that point…

Nancy Barile: Are you answering the question, Al? [Laughs]

Al Barile: No, no, I know, I'm going in the right direction. I backed it up with all this background information because isn't it arrogant for me to say, “Oh yeah, I knew we'd be talking about this one,” you know?

In a way I kind of measured the pulse over the years. That's the best way I can say it. Maybe like 10 years ago we got asked to play a show, someone asked us to play somewhere and offered us $25,000. There’s a bunch of stories like that.

I've been in two bands, and in the second band, I kind of got more involved. We opened up for The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, and I could have used my hardcore cachet or whatever but, at that point, the Bosstones show didn't go that well. I elected to kind of pull back a little bit, just let that band do its own thing, not go there, because I guess after that show I kind of said, “Geez, maybe we're not going to be accepted.” I thought it would be like a natural acceptance, like, oh, I started another band, they’ll like this one too. That was kind of a rude awakening that I was in for a lot of work to get probably one-tenth the popularity of SSD. I mean, I knew all along that I was chasing SSD. With whatever I did, I was always going to be known as a member of SSD.

This is exorcising a lot of these demons here. I realized that I could do anything, I could write the greatest album, five great albums, whatever it was, it wasn't going to make a difference. I was Al from SSD.

So with that, did either of you ever feel like you wanted to remove yourselves from that history? Did you want to make a break from being Al from SSD or Nancy from Philly who booked all the shows?

Al Barile: I never ran from it. I never did. I don't think Nancy did either. After the band broke up, I went to college full-time, and in academic life, it didn’t really come up. During my college career, it came up once or twice, where someone was like, “You’re Al from SSD.”

I'll just say this upfront, and Nancy’s going to answer it, but the only time it comes up where it negatively hurts me is when she's known as Al from SSD’s wife.

Nancy Barile: I mean, that's not something I run and hide from either, you know, but I do like to be my own person. There were people who when they bought my first book thought it was going to be about SSD and Al. And even some of the mansplainers were like, “Oh, you know, you wrote a book on the coattails of your husband.” I was like, “He's barely even in it!” Or to paraphrase Al, because he's never read it: “Am I in your book?” [Laughs]

Al Barile: That stinks when I hear those kinds of stories about people giving her a hard time like that, you know? Because she did it all, this is all her, she did everything for both of those books, so she deserves all the credit.

Nancy Barile: But I mean, it was always something that was inside me and never left. I think a lot of people that came up the same way we did in the early ‘80s, they kind of feel the same way, that punk, hardcore, whatever you learn from that, it kind of stays with you.

Al Barile: What I’ve learned is that I think it gives you courage because I don't have the same courage today. I mean, I can maybe resurrect it once in a while, but sometimes I look back and I can't believe I did that. That kind of courage wasn't natural for me. It might have been natural for her, but it wasn't natural for me, because I really am kind of an introvert.

Nancy Barile: In my career as a teacher, it really helped me so much because it made me so fearless doing a lot of gang outreach and stuff. Those kids would often say to me, “Aren't you scared?” And I wasn’t. One of the kids recently wrote me a letter and he said, “I read your book and now I know why you weren't scared.” It's something that I think just lives inside you no matter how long you're out of it.

One of the things I took away from both your book Nancy, as well as a lot of older interviews and writings about SSD, is that if the thing you wanted didn't exist, you should just make it. Do you ever think about how big of an impact those things made on the people who experienced them at the time?

Nancy Barile: I went to Catholic school and I was a Girl Scout, and my mom was frequently the Girl Scout leader. When we needed a cheerleading coach at school, she became the cheerleading coach. I watched my mom do a lot of do-it-yourself stuff because Catholic schools have no money. When you want to do something, you have to plan and do it yourself. I definitely took those skills that I learned from her when we started doing shows in Philly.

But to me, it was just such a group effort with everybody working together for a common goal. The first time we did Punk Fest I, we didn't even know if anybody would show up because we felt we knew the 50 punks from the Philly and New Jersey area. I can remember when the doors opened and we looked outside and there was just a line down the block going on and on. It was such an incredible feeling like, “Oh my God, where did these people come from?” It was probably 300 people, 400 people there for that first show that we did. Doing those shows, they were always fun but, for me, they were also really scary because there was so much that could go wrong. We were renting from the Elks people and we didn't want to upset them. You know, they were mostly older Black men who had created this fraternal organization because they weren't allowed into the white one at the time. And that was a big community center for the Black community and we wanted to make sure everything went smoothly, nothing got stolen, you didn't want a riot. Those were definitely scary components of doing the shows.

When I did the Black Flag show, I did it with a guy named Lee Paris, who was a DJ at WXPN in Philly, University of Pennsylvania. Just having somebody else to shoulder that, and of course, the band members did too, but just having somebody that you could share the stress with was always really good. Because something always happened. The show I did with Al, he was like, “Don't bring me to a war zone.” That turned out to be the Camden, New Jersey show that was so insane, but great. [Ed. note: This is the infamous Buff Hall show where Ian MacKaye was hit by a car outside before playing with Minor Threat, which is just one of many notable things that occurred that night.]

Al Barile: I don't think I ever consciously said, “Oh, this is bigger than I expected it.” I'd say the bigger question is: why did I think I could do this? Because the real problem was, I don't know if I fantasized, but I thought about this music thing for a long time.

I had a sister, but she was not someone who handed me down anything by showing me her records or anything like that. The only thing I got from her was she took me to my first concert, which was Chicago, but we sat behind the stage and I remember thinking to myself that I couldn't even understand why the band sold tickets behind the stage. This was the Boston Garden and it was ridiculous. I didn't want to sit behind the stage, I wanted to see the action. Then again, Chicago just had a bunch of horns, so there wasn't a lot going on there.

I knew that I wanted to explore this rock thing but I didn't know how to get there. I used to look at kids in class and I knew the ones that played guitar and the ones that were in cover bands. I used to say to myself, “I'm never going to get there. There's no way I'm going to be doing what they're doing.” They had long hair, you could tell they were talking to the girls and stuff like that. I'm like, “I don't see how I'm gonna do this.” But I tell you, I saw the Ramones in the late ‘70s and they definitely inspired me. I was like, “Oh man, maybe I can do this.”

I had my crew of guys that we hung around with after school and played football and street hockey. I was always one of the leaders of the pack, I was the guy that said, “Hey, we're going to do this.” Or when I got my license, “Hey, we're driving to Boston.” I was a guy that set up, I guess, the entertainment for who I was around. I would sell things out of my garage, not to make money, but just to kind of run some carnival games and stuff like that. You know, stupid things that are really embarrassing now when I think about it. If some older person saw this little eight-year-old or whatever doing this stuff, I look back on it and I’m like, “I must've been nuts” because these are stupid things.

Nancy Barile: It's entrepreneurial.

Al Barile: No, my parents should have pulled me aside and said, “I don't know what you're doing here.” I think some of these things I did were definitely in the spirit of entertainment and stuff. But it took me years to figure this out.

I told the story about straight edge and what it meant, but I didn't have a lot of courage. At some point, I definitely went along with the crowd because I wanted to be accepted. And that's really not me. I end up going the other way, rebelling the other way. I was drinking in the woods, doing that kind of thing. Many times I said, “What am I doing this for?" But I still continued to do it just because I didn't want to be left out. So I did things that I don't think were necessarily me. I think that all that time, I was trying to get the courage to speak up and say, “I'm not going to do it.” And I did get the courage finally.

When we met the D.C. people, I saw how they were all X’d up and not drinking, I found a lot of strength in that. I came home and said, “You know, I'm not going to drink anymore.” That's kind of my story of how I decided not to drink, but what really went into that is me getting my voice. I was leaving that life behind. It took a lot of courage to just walk away from all your friends and find new friends, you know?

I thought I was gonna have to put my own shows on because I was lucky to form this band with these people. Once I found the band, putting on shows and then making records was really almost expected because I got past that first hurdle, which was a huge hurdle. But stopping the partying thing was even more courageous because I could have just continued.

A lot of people probably weren't expecting a hardcore punk band in Boston to be straight edge like that. Though I wouldn't call us a straight edge band, because we never called ourselves that, but that certainly was the thing that people were noticing. They caught on to that straight edge thing, almost in a divisive way. A lot of people didn't like it. I’m sure it put a lot of pressure on people, you know? It put pressure on the guy who wrote the song and the bands we played with

Nancy Barile: You're just going off now.

Al Barile: Well, it was a good answer, I thought!

Nancy, you kind of addressed this already about bringing your punk life into your role as an educator, but I’d be curious to hear if you felt you were able to do the same thing in your professional life, Al? It sounds like for both of you, it was something inside of you that wasn’t going to leave.

Nancy Barile: Yeah, 100% for me. I was still listening to music and still going to concerts and stuff up to a certain extent, not as much as I was when I was heavily involved in the scene but I was still listening on my Walkman to Minor Threat and the Bad Brains and stuff. I always carried that with me. It's definitely something that my students, I think, felt about me. I don't look anything like my students. My students are from very different countries and different backgrounds and different races and ethnic groups and I had to connect with them on some level. I can remember one of the kids saying after he had graduated, we were Facebook friends, and I posted some punk rock picture of me because I kept it a secret for maybe, like, my first five-to-seven years, because I was scared. I didn't know how it would play with parents or administrators until some kid outed me. So, I posted that picture of, I think it was a CBGB picture or something, and the kid wrote underneath it, he was like, “I knew it!” So, you know, it was something that they felt, too. It gave me a great connection with them because of it. The “question authority” thing stays with me to this day; a fact that gets me in trouble quite a bit.

In sophomore year, we used to read this book called A Long Way Gone about a soldier in Sierra Leone, and my friend found out that the Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars were going to be playing the Boston Garden. My friend came to me and she said, “Hey, let's get them to play our high school!” I was like, are you crazy? They were on Oprah. They're playing the Boston Garden. They're not going to come here and play our school. And she was like, “Oh, some punk rocker you are” and I was like, oh, so now the gauntlet is thrown. I went on their website and found their manager and we ended up getting them to play our school. It was one of the best days of my career. But again, that's because of that kind of do-it-yourself spirit. I've gotten authors and resources and field trips and everything just based on that do-it-yourself attitude. I've also always wanted to make sure that my students become critical thinkers and problem solvers and they don't fall for a lot of the crap that's out there. I want them to be able to check and evaluate sources and everything. And to me, that no-bullshit kind of thing, being able to see through all that, came from punk rock as well.

Do you feel similarly, Al?

Al Barile: Actually, I can honestly say like me, the Al today, is the same guy back in 1982. I have evolved somewhat, but I haven't in many ways. I'm pretty much the same guy, you know? A big phase of my life was that I went to Northeastern University, and graduated as a mechanical engineer. I started my engineering degree in like ‘88 or ‘89, so those next 30 years I looked at it as the same thing. It was just forming other teams. Because SSD was a team. I started a new team when I was working at my job there.

There were things that kind of bothered me at GE that I thought I could, and I don't want to say I was naive, but things that I thought I could change the world on. I thought that the relationship between the union and me, I was in management when I came in as an engineer, but I'd worked there as a union machinist for three years. I took a leave of absence and went back to get my degree, so I had seen the two different sides of that equation. I thought that I could be the one, now that I'm in management, that could treat the guys in the union a different way, possibly. I definitely felt the way I was treated when I was in the union, it was an us-against-them kind of thing. I said, why isn’t it “we” instead of us against them? It should just be we. During that course of time, that was the attitude I took to work every day that there was a different way.

That job provided some of the same challenges that SSD provided me. I couldn't do my job at GE by myself. I couldn't do SSD by myself. I absolutely knew that during the course of SSD as the thing was progressing. We did a couple records, we added Francois [Levesque], our fifth member, second guitar player, and the third and the fourth album came out. I could see our audience, towards the end, they were not enjoying what we were producing as much as the first two records. I got to witness that and ask if I could correct that. Ultimately, the band broke up, and I got to see and feel that when you work really hard for something and then it fizzles out. I got one more crack at it when I started Gage. I tried to work on all the things that maybe didn’t work out in SSD. I built a recording studio, and I’ve got to thank my wife for letting me do that because I spent a lot of money building that recording studio and launching that band.

As I sit here, a man with cancer, I don’t have any regrets. We had some of the same issues with Gage that we had in SSD, but I don't have any regrets. I spent a lot of money and learned stuff and I’m equally as proud of that band, although no one remembers that band.

When I lost my job, and it's God's honest truth, I was kind of pushed out because of my health. I really started to think about, wow, I don't have a creative outlet right now. My health was sinking really bad—I'm not being light on this—so that's when I started to think about my next project because I always look forward to the projects. I never looked backward, but that was the first time I allowed myself to look backward. I knew around 2017 that I was going to allow myself to look backward on purpose, not for any other reason than just to see if I could enjoy it because I really never enjoyed any of this in life because I always treated it as work; it was my job. I felt like I'd try to see if I could salvage something out of this and see if I could enjoy looking back and maybe reconnecting with it. Because that's the best thing through all this, whether it be my job or whatever, is the connections you build and the people you meet. That's why the record came out, that's why the SSD book came out.

We talked about this SSD book and how Philin Phlash was sitting on this large stash of photographs, and Nancy had a lot of energy and perseverance, and she’d had success on the first book. This SSD book was being talked about for like 20 years. She pushed Phil even harder and got this book to come out. It probably would have been talked about for another 20 years because Phil, we found out later, wasn’t behind the project as much as we thought he was. We thought he was working on the project, but he really wasn’t. Really, Nancy's doing all the work and our publisher's doing some work and, at that last minute, I got involved and did what I do best, which is yell and scream at people and try to make sure the book came out. So that was my role. I should have been more active.

Nancy Barile: It's good that you weren't involved in the minutia because it's better you came in the fourth quarter,

Nancy, you've become a real steward of this legacy in recent years. Before now, there was a lot of mythologizing and storytelling and half-truths, and that can be fun for a while…

Al Barile: Let me jump in, cause I'll forget this if I don't say it right now, but when you say that, I also thought at the same time that I was having this idea that it would be nice even if Springa [David Spring, SSD vocalist] and I could be in the same room. And I thought that I would do these interviews after all these years of saying no because I always just said no or didn’t answer people back, which is even more rude. I was probably rude to so many people, but I just felt like I actually had given a lot of answers that were out there and people just needed to look hard and find them. But I don't think the answers are all out there. Now, I'm kind of spelling it out clearer.

To be honest, I think it needs to be now because I'm not going to be here much longer. That's what I feel. Because you're right, I think if I'm not doing this right now, then I would have left with a lot of misconceptions. So, I want to answer some questions. I mean, these are questions that I have not answered to really anyone. Like, even the band doesn't know some of my innermost thoughts. I'd say even my wife doesn't know some of my innermost thoughts. Well, she might know too much, because I probably talked about them for like the last 40 years.

Nancy Barile: That was another reason as well because academics started getting a hold of the genre and the counterculture and everything and putting their spin on it. In my book, I talk about an article that came out from Drexel University, and they had it so wrong that I was like, “Well, then I'm going to write my first-hand account because this is incredibly wrong.” Right before I started doing it, maybe five years, six years before the SSD book became an idea, I did some interviews and stuff and people would say like, "Oh, didn't this happen with SSD?" I'd be like, no. There's all this crazy mythology of people dying at straight edge shows, which I know later on, years later in Utah or somewhere, it actually did happen, but that was not part of our experience at all and never what anybody wanted. So when academics get a hold of something, and I'm an academic, so, you know, but they can sometimes put spins on things too, so it felt important to have a say in it.

It sounds like what you’re both saying is that it was getting to the point where if you didn’t put your hands on it and get involved right now, there might not be another chance.

Nancy Barile: Yeah, absolutely.

Al Barile: Well, I was going to answer that I could see it going the other way, too. There was no like, “We've got to do it right now or it’s never going to happen.” I don’t think there was any of that. But, because of my health, I realized I only got so much time here. I had cancer last year, and it didn’t accelerate anything with me, but maybe the Trust Records people realize they’ve got limited time or something. So my answer would be, I just want to make sure the record has the right home. Over the years, I've been asked several times to do it. I think around 2010 or 2011, Matador asked to put it out. There have been various periods where I've been approached, and I've thought about it, and in the end, I'm like, the easiest decision is to do nothing. I could have easily done the easy thing again. Maybe Nancy wouldn't answer it that way, but I could easily see nothing happening right now.

Nancy Barile: Yeah, for me it was really important to get it done. Super important, because I was just hearing too much bullshit out there, and I wanted to be on the record with the reality and the facts. That's why, to me, there was a pressing need to get it out.

Al Barile: And I don’t want to say Nancy did this to honor me…

Nancy Barile: Well, I did the SSD book to honor you. Your book was absolutely a labor of love. And again, when I'm running the SSD pages and Facebook pages, and people are writing stuff on there that's so incredibly not true, I thought it was kind of necessary to go on the record.

Al Barile: Yeah, so she's been correcting the record.

Nancy Barile: There’s a difference between correcting the record on Facebook and Instagram and having it out there in a book, told in the words of the people that were there.

Al Barile: I've got to be honest, though. The crazy rumors never really bothered me. Nancy's bothered by things more than me. I just laugh.

Nancy Barile: Well, for me, it was a lot of the woman's role in the scene and people trying to either minimize it, trivialize it, denigrate it, desecrate it, and I wasn't having it, you know? I just was not having that happen. So that was the thing.

I think that’s something that’s always come through from both of you though, that it wasn’t just the bands or these figureheads, but there were a lot of people behind the scenes, or even just people going to shows, who made important impacts on the structure of hardcore. Is that something you still think is important to capture here?

Nancy Barile: Yeah, definitely. Social media brought me in contact with a lot of people that I hadn't talked to in years and I was kind of rebuilding the community through that. But then again, I was seeing a lot of bullshit on social media. But I remember, you know, contacting Ian because I had been away from it and he had stayed in the music business. My question to him was that I wanted him to help me frame my book. Like, why am I still talking about this 40 years later? And it was exactly what Ian said, it was about the hang, it was about the community, it was about the people. It's incredible to me that, to this day, we are still friends with those people. I work with Jamie [Sciarappa], the bass player of SSD, he's an English teacher at my school.

When I went down to Philadelphia for my first book party down there, over 230 people came out for me. I'm just a nobody, and that blew my mind. It was like the high school reunion everybody wished for. It was just so fun to see those people, these friends, that are so loyal to the end and who are such an important part of that time period and are still an important part of my life. To me, it absolutely had to be done. And it was really because I was hearing stuff from academics, stuff from people that came much later, who really had it wrong and I wanted to set the record straight.

Al, to revisit you saying no to so many things, was part of that inspired by your experience giving the Xclaim! stuff over to Taang!, and I know you've had some issues with how they handled things.

Al Barile: Well, definitely the Taang! experience. I never was a big vinyl guy. I actually hated it. I hated how the needle would scratch the record. I hated how the records would warp. As an engineer, I have no love of vinyl at all. Never had it. I hated it.

You’re breaking my heart here.

Al Barile: No, no, I'm going to be honest. As an engineer, I could never accept vinyl. I hated that warpy thing. That killed me. Even when I made my own records, I would put certain songs not on the edge, because if they warp, they'll skip. I was thinking that I’ve got to put the best songs on the inner grooves where it’s more stable. I liked the seven inches because they never warped, but I didn't want to make seven inches because they could only fit a couple songs on there. So we had to make albums.

But with Taang!, CDs had come along and he wanted to do it. Now, I knew at the time that everyone wanted to release The Kids Will Have Their Say and Get It Away. That's what they wanted to release, and I knew that. But my concept was a greatest hits kind of thing, that was the idea, so I could preserve the integrity of The Kids Will Have Their Say and Get It Away. I thought, possibly because things had changed, that the band would be completely forgotten, and I didn't want the band to be forgotten. That was the rationale.

In the end, that’s one of the biggest decisions I regret because I could have done it myself. I really could have. I didn't really get involved in that project to the point of overseeing it. I kind of let those other people do everything and that was a huge mistake. Right now, with putting together these Trust Records releases, we couldn't even find the master tapes. So I know that Curtis [Casella] from Taang! has the master tapes. He's saying he doesn't have them, but when they made [SSD compilation album] Power, he had all the tapes. He inadvertently ended up having tapes that he should not even have been in possession of. When I got some of the tapes back during the ‘90s, I had a Pro Tools setup and I was gonna digitize the records. I asked him to send them back. He sent back all these tapes, these outtakes, and they weren't even the tapes that were on the record. At the time, I didn't have any recording equipment that could transfer them, so I sat on these tapes for a while, and they ended up getting water-damaged in my mother's house.

It's a bad story about bad people. When people are looking for a label to put their music out, they should think long and hard about who they do business with. That story is repeated over and over in the music industry. That's why, in ‘85, I sold all my equipment and bought a jet ski, because I was sick of that whole thing. I didn't like that part of the music business. I didn't trust a lot of people. There are a lot of people in that business that don't write songs and get a lot of money.

On that note, when The Kids Will Have Their Say Came Out, it was through Xclaim! but it also had a Dischord Records catalog number. Clearly, you both are still friends with Ian, so is there a reason that Dischord never re-released it?

Al Barile: You're reminding me, Ian mentioned that he was interested in it, which really took me aback. The way it became half Dischord originally was because I was starting Xclaim! and I thought it would help my credibility and get my foot in the door. I asked him and he said okay. I think I gave him a couple boxes of records. It was a real handshake agreement.

Nancy Barile: Ian doesn’t do contracts.

Al Barile: We were both so new at the time, he’d only put a couple things out. Later on, I heard him in interviews saying that Dischord is a D.C. label, which I didn’t know at the time I asked him. If I had known that, I might not have even asked. So when he finally did ask me, in the last five, six years, I was like, “Are you serious? Dischord is a D.C. label.” I couldn’t really gauge his seriousness, because I couldn’t wrap my head around him being interested. I remember telling him, "Oh man, these tapes are in bad shape. You don't know what you're getting into, you don't want to get involved in it." Once again, I chose to do nothing. But he did show interest.

In the end, the Trust thing came about because I heard about them and it sounded like they were doing what I was thinking about, being almost an archival company. We still maintain some ownership in the record, so we didn’t have to give up complete ownership. We own 49% of the record still, and they treat us with a lot of respect. The record’s done really well, and I think they’re happy with it.

As you said, Trust does a lot to honor and respect these records. Does it feel like now that you finally kind of found the home for the SSD material where it can live on and maybe give it a bit of a boost?

Al Barile: I mean, I did think that this might give you a little boost. I think the timing’s pretty good, with my health and not being able to make some of these decisions, I think they’ve done a good job. This wasn’t a quick decision either. This took two years of negotiating and talking about what this record should look like. During these discussions, I told them that one of the most important things is that I want the vinyl people to be happy. This is as much about them as anything. The people that are going to collect it and trade it, I want to make sure that it’s what they want. I knew I was not going to participate in a lot of those discussions about imprints and colors, that wasn’t my thing. I have my own feelings and inclinations, but I purposely took a back seat and let them handle it because I think they do a good job. So far, the feedback has been really good.

Are there plans to do more of the SSD catalog through them or is this it?

Al Barile: Get It Away is coming out next year. I don’t see how that won’t happen.

There have been some very fraught relationships with former members of SSD. One thing I’ve respected is that it never felt like either of you tried to write them out of this or exclude them. Did that present a struggle in getting these projects finished?

Nancy Barile: Interviewing Springa was the very last thing that I did. It was the very, very last thing. I had everybody done and edited and then I was like, okay, now I get to talk to Springa. [Laughs] It was so typical, too. I put the word out, he called me, and I asked for a block of his time, just a couple hours. He was like, “I’ll call you tomorrow at one o’clock.” At four o’clock, he calls. And I work three jobs, so when I tell you a time, you’ve gotta honor that. But I was like, I have to do this now with him or it’s never gonna happen. And, you know, he was fine, and most of what he gave me was great. We even wanted Francois, but we could not find him. We did this incredible search, and this FBI agent here, Al Barile, found him, but the book had already gone to print. But yeah, if you're going to tell the story, you've got to tell the whole story.

Now that all of this is going to be out in the world, we’ve talked a lot about the people to whom this has meant something over the years, but what do you hope that someone new to the band, or these stories, takes away from them?

Nancy Barile: For me, my kids at school, they don’t really listen to punk or hardcore, there’s maybe one or two. But I’d like the kids to see the book, to see the record, and say, “Wow. They were 19 when they did this.”

Al Barile: When they see those things, they should see that you can do anything really.

Nancy Barile: That's what I want my kids to see. You should be out there you should be doing this. You should be having fun, being creative, sharing your feelings, and using your voice through whatever medium that you want. Whether it’s a podcast or writing or music, you should be out there doing it and saying it and making it happen.

Al Barile: It’s interesting that you asked this because I don’t think I really know the answer to this question. Be it the book or the re-release of the record, all this time when people would say, “Why don’t you re-release the record,” I’d ask them, "Why? There has to be a reason why we’re doing that." I think this interview has answered that. I’ve allowed myself to reflect a little bit and smell the roses, so to speak. The fact there’s interest allows us to do this. If there’s no interest, then it’s pointless. We’re lucky that we can do it.

But for me, it’s really all about my health. At this point in my life, it’s probably the last phase of my life, it’s that timing for me. There’s part of doing this now where, in a way, if I’m not here much longer, I get to live a little bit longer.